Finland/Sweden comparison: No great differences in working among mothers of small children

The employment rate is not the best indicator for comparing working among parents of small children. Measured by the work attendance rate, Finnish and Swedish women go to work almost equally much. However, there is a clear difference for mothers of children aged under three.

The employment rate is not the best indicator for comparing working among parents of small children. Measured by the work attendance rate, Finnish and Swedish women go to work almost equally much. However, there is a clear difference for mothers of children aged under three.

At the moment, much attention is paid to employment of parents of small children – of both mothers and fathers. The family leave system raises discussion and various bodies from political parties to interest groups have presented their models on how to renew family leaves.

The employment of mothers of small children has raised special concern. It has been thought that long absences from work impair both mothers’ career advancement and income level and reduce their pension. Often the point of comparison has been sought from Sweden; Swedish mothers appear to be working more frequently than Finnish mothers when children are small.

The comparison between the countries is hampered by the differing statistical method, as Swedish statistics consider persons on parental leave to be employed and Finnish statistics sees them as non-employed. For this reason, examining only employment rates does not give a clear picture of the differences between the countries particularly for mothers of small children. In addition, the family leave systems are different, which in part makes the comparison difficult.

This article examines the labour force participation of parents of small children in Finland and Sweden using other indicators such as the work attendance rate and share of part-time work, in addition to the employment rate.

Work attendance rate takes into account temporary absences of employed persons

In Finland’s Labour Force Survey employed are those who have worked for at least one hour during the survey week. Employed are also those employees absent from work in the survey week who have a job and whose reason for absence is maternity or paternity leave, illness or accident or whose absence has lasted under three months. Self-employed persons are always included in employed even if they had not worked during the survey week.

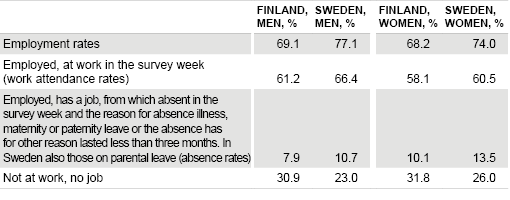

Thus, employed include both those who have been at work during the survey week and those who have a job but have been temporarily absent from work. Because the countries have different statistical methods and varying family leave systems, we should specifically compare persons who were at work during the survey week. The concept used for this share of persons who were at work during the survey week is the work attendance rate. The share is calculated from people of working age. This is illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1 presents employment rates for the countries and, on the one hand, the shares of those having been at work during the survey week and, on the other hand, those having been absent from work among the working-age population. As the table shows, a bigger share of employed persons have been temporarily absent from work in Sweden. The reason for this may have been annual leave, parental leave, illness, accident or studying.

Table 1. Employment rates, work attendance rates and absence rate, aged 15 to 64, 2015

Sources: Labour Force Survey, Statistics Finland and SCB

The work attendance rate as an indicator of working narrows the difference between Finnish and Swedish women to around two percentage points, while measured by the employment rate, it is nearly six percentage points. For men, the corresponding difference contracts to around five percentage points – measured by the employment rate, the difference is eight percentage points.

Measured by both the employment rate and the work attendance rate, Finnish men’s difference to Swedish men is bigger than the corresponding differences with various indicators for women. Finnish men fall more behind Swedish men in employment than women do.

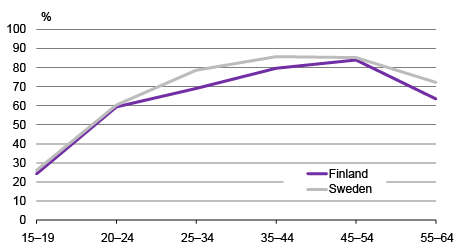

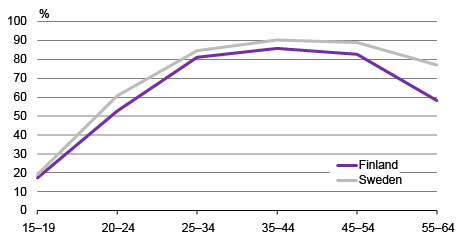

The matter ought to be examined by age group to see what effect different life stages have on employment. Figure 1 shows women's employment rates and correspondingly, Figure 2 work attendance rates by age. As the figures illustrate, there is a difference in employment rates between countries particularly in age groups 25 to 34 and 34 to 44. The difference is also comparatively large among those aged 55 to 64.

Figure 1. Women's employment rates by age, 2015, %

Sources: Labour Force Survey, Statistics Finland and SCB

Figure 2. Women's work attendance rates by age, 2015, %

Sources: Labour Force Survey, Statistics Finland and SCB

In contrast, there is not much of a difference among the countries in the work attendance rates except for the oldest age group (Figure 2). Measured by the work attendance rate, Finnish and Swedish women go to work almost equally much.

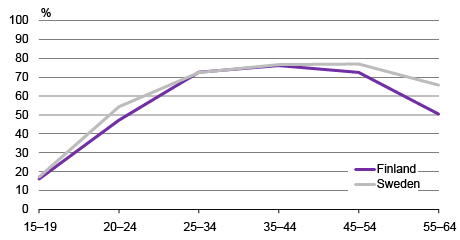

The corresponding data on men are found in Figures 3 and 4. Unlike women, men's difference in the employment rate remains when employment is examined by means of the work attendance rate. Attention is turned to Finnish men aged over 45, whose employment is clearly lower than that of Swedish men measured by both indicators.

Figure 3. Men's employment rates by age, 2015, %

Sources: Labour Force Survey, Statistics Finland and SCB

Figure 4. Men's work attendance rates by age, 2015, %

Sources: Labour Force Survey, Statistics Finland and SCB

Difference evens out for parents of children aged over three

Next we examine working among parents of small children. Because Finland and Sweden produce statistics on parents absent from work in varying ways, we have compared only those who were at work during the survey week, that is, work attendance rates.

Figure 5 shows the work attendance rates of parents of small children, for both fathers and mothers, by the age of the youngest child. Among parents of children aged under one, slightly more Finns than Swedes go to work. Correspondingly, Swedes pull ahead of Finns when the youngest child is aged one to two.

Figure 5. Parents’ work attendance rates by age of youngest child, 2015, %

Sources: Labour Force Survey, Statistics Finland and SCB

When the child is aged three, the difference between the countries evens out. There does not seem to be great differences in the work attendance rates between the countries when we look at the activity of both parents together.

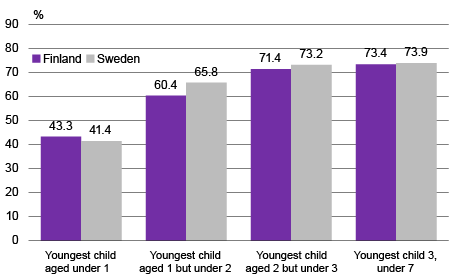

Differences between countries are revealed when we look at mothers’ and fathers’ work attendance rates separately. Figure 6 shows that in both countries the mother appears to be the primary carer of a child aged under one.

However, it is more common in Sweden for mothers to return to work when the child is one year old. Finnish mothers’ work attendance rate is lower than that of Swedish mothers especially when the child is aged one to two (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Mothers’ work attendance rates by age of youngest child, 2015, %

Sources: Labour Force Survey, Statistics Finland and SCB

At the stage when the child is two to three, the difference between the countries is around ten percentage points. The difference in work attendance rates levels off quite fast. When the child is aged three to six, Finnish and Swedish mothers already go to work equally much.

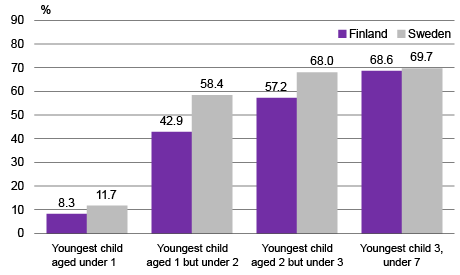

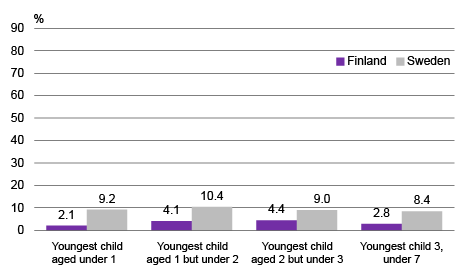

The situation is opposite for fathers (Figure 7). Working among fathers of small children is more common in Finland than in Sweden. The difference is around seven percentage points when the child is aged under one year and when the child is aged two to three. The difference in the work attendance rates evens out for fathers as well when the child is aged three to six.

Figure 7. Fathers’ work attendance rates by age of youngest child, 2015, %

Sources: Labour Force Survey, Statistics Finland and SCB

Based on these figures, we can conclude that there is not much difference between the countries as to how much parents of small children go to work in the first place. However, Swedish parents appear to share child care more evenly between the parents than Finns do.

Swedish parents work part-time

In addition to the work attendance rates, we also ought to examine how much work is done when children are small. How much do Finns and Swedes work part-time?

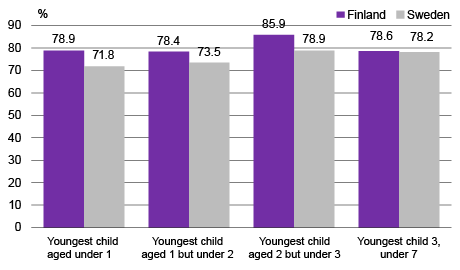

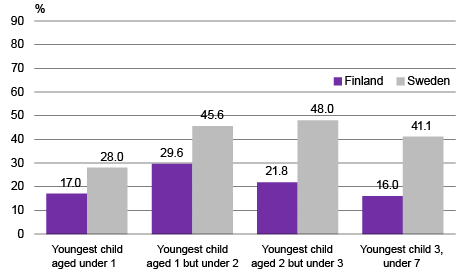

Mothers’ and fathers’ part-time work is explored in Figures 8 and 9. The share of those working part-time is calculated from employed persons. Swedish mothers work clearly more part-time irrespective of the child's age, while in Finland part-time work is more clearly connected to the child's age.

Figure 8. Mothers working part-time by age of youngest child, 2015, %

Sources: Labour Force Survey, Statistics Finland and SCB

Figure 9. Fathers working part-time by age of youngest child, 2015, %

Sources: Labour Force Survey, Statistics Finland and SCB

In Sweden, over 40 per cent of mothers work part-time even when the child is aged three to six. In Finland, the respective share is only 16 per cent. The share of women working part-time on the whole is clearly higher in Sweden: 32.8 per cent of women aged 20 to 49 work part-time, of Finns of the same age just 16.2 per cent.

The same can be detected when looking at fathers. Part-time work is many times more common for Swedish fathers than for Finnish fathers when children are small.

Working time flexibility may steer permanently into part-time work

Finland is often compared with Sweden, so interest is also paid to how parents of small children go to work in different countries. In this article, the work attendance rate is used as the indicator for working because the comparison of employment rates is not sensible for all groups due to the differing statistical methods.

It is interesting that when comparing the work attendance rates the difference produced by the employment rates between Finland and Sweden narrows down – for women it even disappears completely except for the oldest age group.

Measured by both indicators, Finnish men's difference to Swedish men is bigger than Finnish women’s difference to Swedish women. Finnish men's employment rate is below the EU average and correspondingly, women’s employment rate is above the average.

Another conclusion is that parents of small children go to work as much in both countries. However, there is a distinct difference in working among mothers and fathers between the countries.

Finnish mothers go less to work than Swedish mothers and correspondingly, Finnish fathers are more at work than Swedish fathers when children are small. The differences in working among both mothers and fathers between the countries even out at the time when the child is three to six years old.

The third point is that in Sweden, both mothers and fathers work more part-time than in Finland. In particular, Swedish fathers appear to have more time to their family when children are small.

Part-time work functions as a means of working time flexibility when children are small for both parents. Quite a large part (41%) of Swedish mothers continue working part-time even when the child is aged three to six.

One might thus ask whether working time flexibilities steer Swedish mothers permanently towards part-time employment. In any case, having a child is reflected on the work careers of both mothers and fathers in various ways in different countries.

Anna Pärnänen and Olga Kambur are employed at the Population and Social Statistics Department at Statistics Finland.

Avainsanat:

Miksi tätä sisältöä ei näytetä?

Tämä sisältö ei näy, jos olet estänyt evästeiden käytön. Jos haluat nähdä sisällön, tarkista evästeasetuksesi.